PUPILLE

Ci fioriscono gli occhi se ci guardiamo

A cura di Rita Selvaggio

OPENING: Sabato 5 novembre 2022

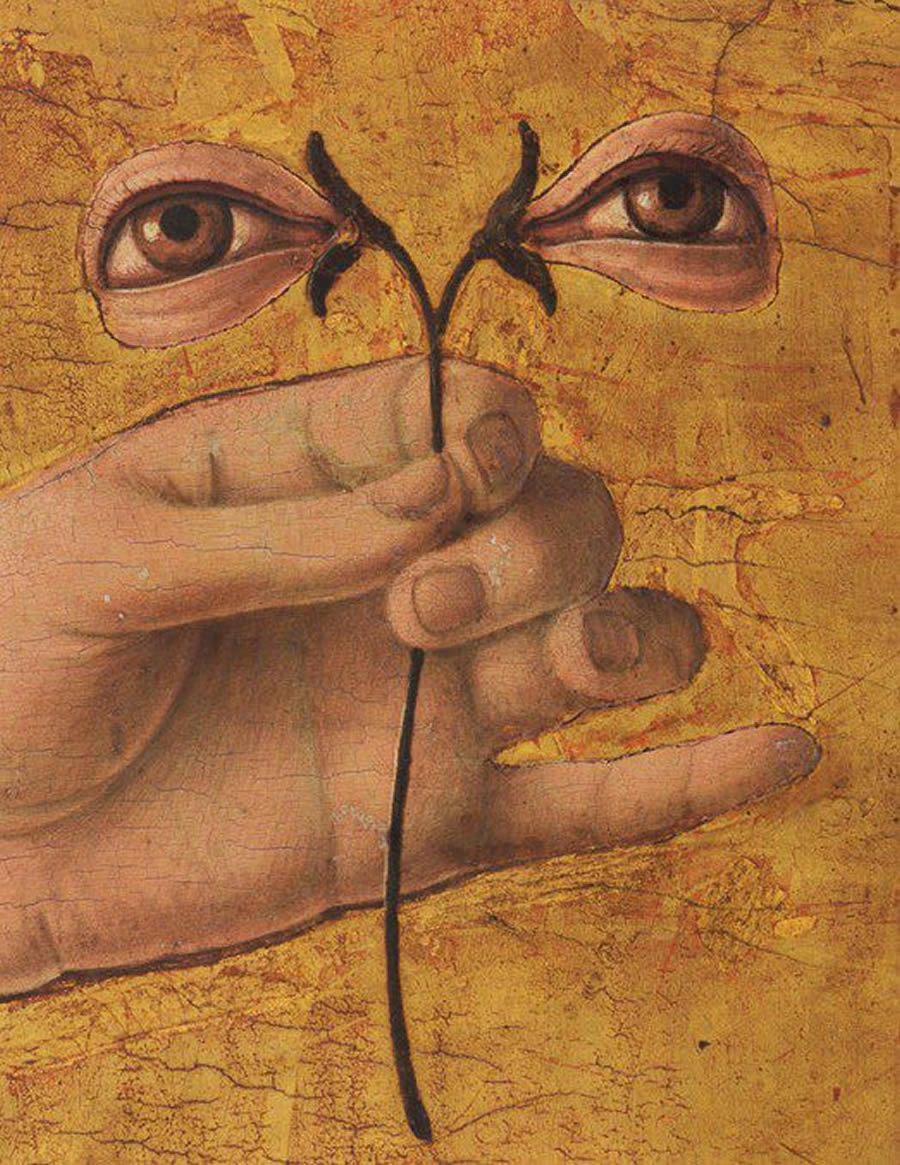

Francesco del Cossa (Ferrarese, c.1436 -1477/1478), Santa Lucia,1473-1474, tempera su tavola, 77.2×56 cm, Washington, National Gallery of Art. Samuel H. Kress Collection. Particolare.

ARTISTS: Aviva Silverman, Emily Sundblad, Isabella Costabile, Jenna Gribbon, Kaari Upson, Karen Kilimnik, Nathalie Djurberg e Hans Berg, Paloma Varga Weisz, Rachel Rose, Trisha Donnelly, Vera Portatadino

PUPILLE. Ci fioriscono gli occhi se ci guardiamo

La pupilla è l’apertura centrale che l’iride presenta nella sua parte mediana e per la quale passano i raggi luminosi per giungere al cristallino. Originariamente un latinismo, diminutivo di “pupa”, ossia bambola, bambina. Quando si guarda una persona negli occhi, il nero lucido della sua pupilla ci rende la nostra stessa immagine, ossia una figurina umana. Il che vuol dire che prima dell’invenzione degli specchi, ci si poteva guardare solo nello sguardo dell’altro. Questo modo per indicare ciò che ci permette di vedere, è reperibile anche nel greco antico; infatti, kore è utilizzato per indicare sia una fanciulla che la pupilla, sancendo una profonda unione tra questi due concetti.

Kore, la fanciulla ineffabile, o “la ragazza indicibile” come definisce questa figura Giorgio Agamben, mito greco che racconta una storia infera e al contempo solare e che, per la sua intima connessione ai misteri eleusini, si legava al silenzio (il termine “mistero” viene da una radice che significa “chiudere la bocca, ammutolire”).

Il sottotitolo cita un frammento iniziale di una poesia di Else-Lasker-Schüler (1869-1945), nella cui opera lirica gli occhi si pongono come centro di coscienza e luogo d’incontro tra l’anima e il mondo visibile.

La mostra persegue alcuni temi presenti in “Masaccio e Angelico. Dialogo sulla verità nella pittura” in corso presso il Museo delle Terre Nuove e il Museo della Basilica. Un dialogo che, in questo caso, si nutre di sguardi: Maria e l’Angelo nell’Annunciazione, la Madonna e il Bambino, il guardare e il guardarsi, le pulsazioni dello sguardo stesso o l’entrare nello sguardo dell’altro e “lasciarsi andare alla chiamata dell’angelo”. In una corrispondenza di sinergie estetiche e concettuali: sguardo | pupilla | kore | fanciulla, il percorso espositivo orchestra un dialogo sullo sguardo in cui i concetti del “Femminile” coinvolgono artiste di diverse generazioni inclini alla rappresentazione del corpo e alle sue metafore e metamorfosi che in questa occasione specifica si misurano con la storia e la storia dell’arte del territorio.

ON GOING ON LINE:

MISTICHE – CUORI SACRI. Ebbre di desiderio, prive di tutto

FLORILEGIO

a cura di Rita Selvaggio e Sofia Silva

Ricerca Iconografica e Apparati: Chiara Di Maria, Valentina Rubino

27 ottobre 2022 – 26 gennaio 2023

Si tratta di due antologie digitali che, in formato newsletter a cadenza settimanale, si intrecciano e accompagnano la mostra per tutta la sua durata.

MISTICHE – CUORI SACRI. Ebbre di desiderio, prive di tutto

Frammenti letterari, documenti, approfondimenti storici intorno al misticismo medievale e non solo, in relazione all’economia, culturale e visiva, del marginale. Insieme agli interventi di artisti, pensatori e studiosi vengono proposte testimonianze di sante e monache, da Angela da Foligno a Santa Veronica Giuliani a Ildegarda di Bingen – farmacista di Dio – ; interventi di intellettuali quali René Guénon a proposito dell’iconografia del cuore raggiante e fiammeggiante. Si ripercorrono i passaggi più commoventi di grandi scrittrici attratte dal misticismo tra cui Simone Weil e Cristina Campo. Le narrazioni della mostra PUPILLE scorrono in parallelo a quelle dei programmi on-line, affinché il pubblico disponga di un intero vocabolario per ascoltare il rapporto tra il sacro, il femminino, il desiderio che si esprime in trascendenza, la visionarietà di una spiritualità che trascende l’individuo.

Philippe de Champagne (Bruxelles,1602 – Parigi,1674), Sant’Agostino cardioforo, 1645-1650, olio su tela, 78.74×62.23 cm, Los Angeles, County Museum of Art. Particolare.

“Sagittaveras tu cor meum charitate tua”

Agostino, Confessioni, 9,2,3

“Hai trafitto il mio cuore con il tuo amore” scrive Agostino rivolgendosi a Dio. Iconografia frequente nella pittura di XVII secolo, il santo “cardioforo” è colui che tiene in mano un cuore “infiammato” o trafitto da una freccia, come segno di profondo amore per Dio. La più conosciuta tra le iconografie di questo genere è quella di Sant’Agostino di Ippona (354-430). L’immagine che presenta il ciclo MISTICHE – CUORI SACRI è per l’appunto un dettaglio di Agostino “cardioforo” dal pittore francese Philippe de Champaigne (1645-1650). La verità della Rivelazione accende le fiamme attorno al cuore pulsante del santo, attraversandone lo sguardo e alimentando così l’attività di studio delle Sacre Scritture. Gli occhi di Sant’Agostino osservano direttamente quella «tenebra luminosa», come descritta da Giovanni della Croce, la luce informe ne attraversa le pupille e la mente, lasciandolo con le labbra appena schiuse.

MISTICHE – CUORI SACRI intende ricostruire il momento dell’estasi attraverso le parole di molti spiriti illustri che si sono espressi in epoche diverse anche attraverso i loro riti domestici, nonché le loro spinte pulsionali e sacrificali. La monaca e mistica francese Santa Margherita, che si distinse nella sua vita per la particolare devozione al Sacro Cuore di Gesù, tanto da ispirarne la festa, si esprimeva quasi lo avesse dinanzi agli occhi: «Ho visto questo Cuore divino come in un trono di fiamme, più brillante del sole e trasparente come cristallo».

In FLORILEGIO, il discorso sul misticismo incontra il simbolismo dei fiori e il significato che essi ricoprono in pratiche religiose, artistiche o curative.

Joos van Cleve (Kleve,1485 – Anversa,1541), Madonna con Bambino, 1530-1535, olio su tavola, 61.1×46.4 cm, Cincinnati Institute of Fine Art. Particolare.

Florilegio, dal latino florilegium – composto da flos floris “fiore” e da legĕre “cogliere” –ossia “raccolta di fiori” prende le mosse dall’attività letteraria di padre Giovanni Pozzi, sacerdote, frate cappuccino, autore di un florilegio. «Un chiuso giardino è mia sorella, mia sposa» (4:12) recita il Cantico dei Cantici in un passo da sempre associato alla Vergine Maria e alla sua purezza. Nell’Hortus Conclusus i fiori venivano prevalentemente scelti per il loro carattere simbolico legato a Maria, madre e generatrice di Gesù e dispensatrice della grazia e di tutte le virtù. Il giglio, fiore bianco, sta per la purezza, l’innocenza e la verginità; la rosa senza spine rappresenta la Sulamita mai toccata dal peccato originale; le viole, emblemi di modestia e umiltà, stanno per la promessa del Regno celeste; il bucaneve rappresenta la primavera e dunque la speranza. L’aquilegia invece ricorda la colomba dello Spirito Santo, come anche il garofano – il cui nome latino Dianthus, deriva dal greco e significa “fiore di Dio” – che per la sua forma e il suo colore è legato alla Passione.